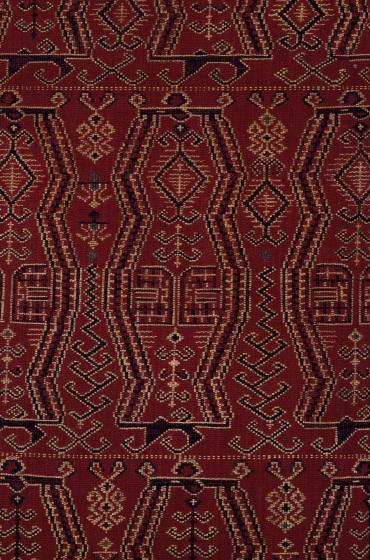

This pua kumbu is an exceptionally fine early example of Dayak Iban ceremonial cloths made for headhunting and shamanic purposes.

There are many sources of inspiration for motifs and designs on the pua kumbu. Dreams are an important source, and motifs often represent elements from a person's dreams. Dreams can be the source of inspiration, or they can let a weaver know that the gods have given her permission to weave a potent design. There is, however, no way of proving that you have had a dream, but a weaver is warned that she treads a dangerous path if she attempts to make a powerful cloth without permission from the gods. The consequences are largely unspecified, but they include being cast into a state of stupor. Weaving a potent design therefore is evidence of blessings and a good relationship with the gods.

Combined with images from real life events and encounters, the pua kumbu expresses a person's fears, hopes or aspirations. The vast canon of Iban mythology and oral history is another rewarding source of inspiration. Many pua kumbus depict episodes from mythology, as well as the adventures of heroes and goddesses, demons, giants and gods.

Motifs on the pua kumbu have intrigued researchers, and a few have tried to analyse them. A systematic analysis of the motifs, however, has proved difficult. This is because, contrary to perception, the motifs are not a form of hieroglyphics nor are they symbols - they do not have universal or stable meanings (Gavin, 2004). The motifs are, instead, whatever the weaver says they are.

A cloth is a very personalized expression of creativity, and although some motifs appear similar, and a few individual motifs may even have specific names, (like deer, clouds, spider or demon), it is impossible for people to guess, with any degree of accuracy, the true meaning of a particular pua. Designs are like people's names - you cannot guess a name just by looking, you have to ask someone who knows (Gavin, 2004).

Innovation is highly valued by the weavers and the Iban community, and this quality is transferred to the pua kumbu. Consequently, the hallmark of an excellent pua is one that demonstrates creativity and ingenuity. Pua kumbu motifs were not simply passed down, unchanged, through the generations. Some motifs may, in fact, be the copyright of an individual weaver, and she can pass those on to her heirs. In a few cases, some particularly fine antique pua kumbus have been copied, for learning purposes and to preserve their designs. However, rather than simply copying designs from existing puas, a weaver would generally attempt to find new ways to put her unique interpretations and expressions into each pua.

The Ibans have a vast canon of oral literature and these stories form the inspiration for motifs and designs. An ingenious weaver would weave her own biography and her dreams into established stories derived from the canon. By demonstrating her expertise in manipulating stories and metaphors from the canon, in combination with details from her personal life, the weaver expresses her personality, including her ambition, yearning, or her fears onto each cloth she makes.

Relatively safe designs depict jungle vegetation, like vines, creepers, trees and bamboo. They were historically, the first motifs a novice weaver made. Potent and dangerous designs depicted human, demon and animal totem figures, like crocodiles and serpents. The human-like figures are called engkaramba. Some motifs, like centipedes, form a protective barrier. They keep malevolent and powerful motifs within the enclosure of the barrier. This enclosure prevents their power from spilling over the barriers on the cloth and in turn harming the weaver and her family.

Historically, puas depicting figures were made only once a weaver had achieved a high status. Today however, because these designs are in greater demand by collectors, the previous taboos are not as strictly adhered to. Consequently, pua kumbus with figures are more common.

Four hundred years ago, the Ibans began migrating from the Kalimantan hinterlands, over the central mountain ranges that divide Borneo, into what is now known as Sarawak. Their movement followed the main arterial rivers, and fanned out in a general direction from the west to the east. Their violent expansion through the landscape displaced other tribes already resident there, namely the Kayans and Kenyahs. Today, the Ibans form the biggest racial group in Sarawak. The Dayak Ibans continue to associate themselves with the river systems they originate from as a way of differentiating the various branches of Iban identity. For example, it is common for an Iban to be called a Saribas river Iban or a Balleh river Iban.

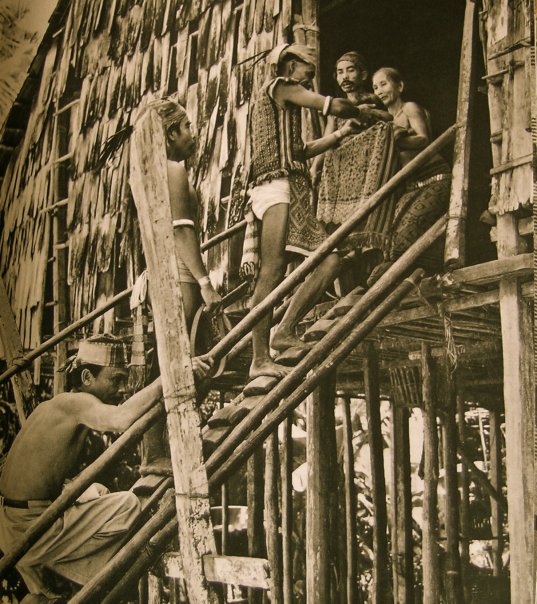

In the past, the pua kumbu was interconnected with headhunting. This interconnection between the parallel activities of headhunting and pua kumbu weaving, is demonstrated by the fact that a significant part of the process of weaving, (the mordanting of the yarns, prior to dyeing), is called women's headhunting. The chain of events, triggered by the cloth, began with inciting the men to venture out and prove their bravery by going out on headhunting expeditions. When the men returned with trophy heads, the women would greet the triumphant warriors, using the pua kumbu as a central prop in an elaborate welcoming ceremony that would last for days.

Another important historical use for the pua kumbu was to act as shamans' 'wings' in healing ceremonies. An Iban shaman was a medicine man and a spiritual guide. In Iban religion, it was believed that a person's soul could become disembodied and lost in the otherworld – an alternative realm to earth. In order to capture and return the soul safely back to the patient, a shaman had to leave the earthly realm and traverse the gap between earth and the otherworld. The means of travel to the spiritual world was the pua kumbu cloth. The shaman would drape the cloth over his body, and it would be 'fastened' to his shoulders using the 'hooks' that were tattooed on his shoulders specifically for this symbolic purpose.

In recent years, these old practices, namely headhunting and shamanism, have diminished, but the cloth continues to be made. Only now the cloth carries different meanings and is used for other purposes. For example, some Iban elites have begun using the cloth to symbolize a distinct indigenous identity, separate from the majority Muslim Malay citizens in Malaysia. The cloth signals a personal and cultural connection to the history of Sarawak. The pua kumbu, which circulates in the international art market, now also demonstrates wealth, taste and refinement. Today, some women artisans are able to earn an income from selling their artwork overseas. For these weavers, the cloth can symbolize fame, status, renown and the ability to participate in the global art market. At the state and national level, the pua kumbu has been used to represent tribal cultures and to promote a message of a harmonious multicultural Malaysian society, by the Sarawak State and national Malaysian tourism boards.